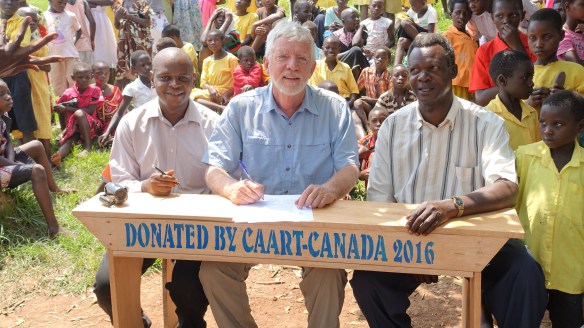

Primum non nocere – first of all, do no harm” was a dictum that I learned in medical school and always tried to apply in day to day practice. I remind myself of this principle, as well, in my role as a trustee of the CanAssist African Relief Trust, an African charity that has consumed much of my energy over the last few years.

There are two schools of thought about providing development aid to some struggling parts of the world.

Peter Singer puts forth the argument that we are morally obliged to help. If we see someone straining to survive and helping them would be of little significant consequence to our own well-being then we must. Most of us would not hesitate to wade into a shallow pool to save a drowning child, even if it meant getting our new leather shoes wet and dirty. Taken more broadly, giving up the cost of a night out at the movies to help vulnerable children in Africa follows the same moral responsibility. A life saved is a life saved, whether in a Canadian water park or a Ugandan village.

Peter Singer puts forth the argument that we are morally obliged to help. If we see someone straining to survive and helping them would be of little significant consequence to our own well-being then we must. Most of us would not hesitate to wade into a shallow pool to save a drowning child, even if it meant getting our new leather shoes wet and dirty. Taken more broadly, giving up the cost of a night out at the movies to help vulnerable children in Africa follows the same moral responsibility. A life saved is a life saved, whether in a Canadian water park or a Ugandan village.

Other writers wonder whether some forms of developmental aid are doing more harm than good. A recent documentary, Poverty Inc, refers specifically to the tons of rice that poured into Haiti after their disaster in 2010. This aid was certainly helpful for crisis relief but it continued to flow into Haiti after the crisis was over. Free rice, bought from suppliers in the US and subsidized by the US government to provide “aid”, caused the farmers in Haiti who previously sold rice locally to go bankrupt. Who would pay for rice at the market when you can get it for free? This ongoing supply undermined the local economy and increased dependency while American suppliers were being paid. There is a difference between humanitarian aid and ongoing developmental funding.

This debate challenges me to think about what we do through the CanAssist African Relief Trust. How can we satisfy our moral obligation to help struggling communities but not create or foster dependency? Like the primum non nocere dictum, it is partly what we don’t do that is important.

First of all, CanAssist does not send goods; we send money. We don’t flood the East African market with materials purchased in Canada and shipped overseas at great cost.

First of all, CanAssist does not send goods; we send money. We don’t flood the East African market with materials purchased in Canada and shipped overseas at great cost.

CanAssist does not deal with large multi-layered governmental departments but directly with individual schools, support groups and clinics. We don’t go to a community to promote our own agenda or ways of doing things. We let the community, school, health facility come to us with their ideas of what sustainable infrastructure we can fund that will improve their well-being.

We don’t send unskilled volunteers to Africa in a “voluntourism” holiday to build a school or do other work that can be done more effectively by Africans. Our supporters don’t rob jobs from local carpenters and masons who need that work to pay for their family’s schooling or health needs. Instead, our funding stimulates the local economy, albeit in a small way.

We don’t provide money for programming, staffing or other individual support. Once a donor starts paying for school fees for a young child, for example, the student becomes dependent on the benefactor’s help to finish secondary school, and beyond. It becomes difficult to stop this individual aid. And only one person benefits from this well-meaning generosity. CanAssist provides communities with funding for sanitation or clean water, or for classrooms and furnishings at rural schools. The materials are purchased locally and construction done by employing local workers, both men and women. If parents are healthy, better educated and have work available, they can earn the money to look after their children. CanAssist project funding, therefore, provides two benefits – temporary employment for local people and infrastructure improvement to the community, benefitting many rather than just one or two.

We don’t provide money for programming, staffing or other individual support. Once a donor starts paying for school fees for a young child, for example, the student becomes dependent on the benefactor’s help to finish secondary school, and beyond. It becomes difficult to stop this individual aid. And only one person benefits from this well-meaning generosity. CanAssist provides communities with funding for sanitation or clean water, or for classrooms and furnishings at rural schools. The materials are purchased locally and construction done by employing local workers, both men and women. If parents are healthy, better educated and have work available, they can earn the money to look after their children. CanAssist project funding, therefore, provides two benefits – temporary employment for local people and infrastructure improvement to the community, benefitting many rather than just one or two.

CanAssist’s administrative expenses in Canada are about 5% of our budget. For some other development programmes, a large proportion of the claimed development funding stays in Canada, paying for salaries, airfares, office space, fax machines, hotels and computers. CanAssist does have obligatory administrative expenses like bank fees, Internet access, postage and liability insurance and some unavoidable professional fees we can not get pro bono. All other goods and services are purchased in Africa. We pay no Canadian salaries. We provide casual employment to some Africans to help implement our projects but this, too, provides initiative to them to work to earn their money. It is not a handout.

We don’t fund one group indefinitely. CanAssist attempts to give a school or community a kick-start to help their development but ultimately they must figure out how to manage their own operational and infrastructure needs. The goal is self-sufficiency and this would not be attainable if the group could rely on CanAssist support indefinitely.

For these reasons, I am convinced that that CanAssist can continue to provide help without harm African communities. We are grateful to our many generous donors who participate confidently in this mission with us – knowing that they can help without fostering dependency.

The Storefront Festival converted empty spaces into unique venues that offered a wide range of productions over about 10 days. My favourite was Cul de Sac, a Daniel MacIvor play. In this one woman show, Anne Marie Bergman, under the direction of Will Britton, presented an engaging story told by several memorable characters. And they were characters indeed.

The Storefront Festival converted empty spaces into unique venues that offered a wide range of productions over about 10 days. My favourite was Cul de Sac, a Daniel MacIvor play. In this one woman show, Anne Marie Bergman, under the direction of Will Britton, presented an engaging story told by several memorable characters. And they were characters indeed. For a few weeks, I worked with a group of Kingston theatre friends on a Single Thread production of Ambrose – Re-imagined. I loved this unique theatre experience last year when it was presented for the first time so I was delighted when creator Liam Karry asked me to join the cast for this newly re-imagined version. Liam likes to surprise audiences and have them experience theatre in non-traditional settings. In this show, audience members made a journey through many hidden areas of the Grand Theatre to meet up with characters who have had some connection to the mysterious Ambrose Small. Ambrose was an Ontario Theatre magnate who disappeared on December 2, 1919 the day after receiving a million dollars for the sale of the many theatres in Ontario that he owned, including Kingston’s Grand. His spirit is known to haunt the theatre with many people over the years, actors and employees, having had a ghostly experience in the Grand. The mystery of his disappearance was never solved.

For a few weeks, I worked with a group of Kingston theatre friends on a Single Thread production of Ambrose – Re-imagined. I loved this unique theatre experience last year when it was presented for the first time so I was delighted when creator Liam Karry asked me to join the cast for this newly re-imagined version. Liam likes to surprise audiences and have them experience theatre in non-traditional settings. In this show, audience members made a journey through many hidden areas of the Grand Theatre to meet up with characters who have had some connection to the mysterious Ambrose Small. Ambrose was an Ontario Theatre magnate who disappeared on December 2, 1919 the day after receiving a million dollars for the sale of the many theatres in Ontario that he owned, including Kingston’s Grand. His spirit is known to haunt the theatre with many people over the years, actors and employees, having had a ghostly experience in the Grand. The mystery of his disappearance was never solved.

In mid August I also took in a Single Thread production of Salt Water Moon that was “staged” on the steps of the University Club, outdoors on a sultry summer evening. This is a great little play and was wonderfully presented. The setting was absolutely perfect for this piece.

In mid August I also took in a Single Thread production of Salt Water Moon that was “staged” on the steps of the University Club, outdoors on a sultry summer evening. This is a great little play and was wonderfully presented. The setting was absolutely perfect for this piece. Firstly, this had the potential to be a huge security risk. Over 25,000 people jammed into a market square and flowing into the neighbouring streets and the Prime Minister glad-handing people in the street would not only be a terrorist’s dream in some places but the potential for a few drunk yahoo’s to disrupt it was almost unavoidable. But it didn’t happen. The crowd was orderly and … Canadian. Yes there was the occasional, or not so occasional, waft of marijuana. But that only led to more singing and dancing and air-guitaring. There was security around but not that evident. No guns on display. People checking bags at the entry points to the venue were wearing t-shirts, not uniforms. Everyone was polite. The energy was all celebratory.

Firstly, this had the potential to be a huge security risk. Over 25,000 people jammed into a market square and flowing into the neighbouring streets and the Prime Minister glad-handing people in the street would not only be a terrorist’s dream in some places but the potential for a few drunk yahoo’s to disrupt it was almost unavoidable. But it didn’t happen. The crowd was orderly and … Canadian. Yes there was the occasional, or not so occasional, waft of marijuana. But that only led to more singing and dancing and air-guitaring. There was security around but not that evident. No guns on display. People checking bags at the entry points to the venue were wearing t-shirts, not uniforms. Everyone was polite. The energy was all celebratory. Secondly, our Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, an acknowledged Hip fan was there to celebrate with us. He walked through the mob in Market Square just before the concert and shook hands and took selfies and smiled in his jean jacket and Tragic

Secondly, our Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, an acknowledged Hip fan was there to celebrate with us. He walked through the mob in Market Square just before the concert and shook hands and took selfies and smiled in his jean jacket and Tragic Last, but not least, was the courage and determination and resolution that Gord Downie showed in not wallowing in his sorrow and illness but living life to the fullest despite a dismal prognosis. I was tired from standing the three hours for the concert in the square., How exhausted must he have been after dancing and singing his way through the concert, the last of several this month, despite his recent surgery, radiation and chemo treatments for his cancer. This, to me, was really something incredible and an example to all of us not to give in to our troubles, but to live every moment fiercely. We are all dying at some point.

Last, but not least, was the courage and determination and resolution that Gord Downie showed in not wallowing in his sorrow and illness but living life to the fullest despite a dismal prognosis. I was tired from standing the three hours for the concert in the square., How exhausted must he have been after dancing and singing his way through the concert, the last of several this month, despite his recent surgery, radiation and chemo treatments for his cancer. This, to me, was really something incredible and an example to all of us not to give in to our troubles, but to live every moment fiercely. We are all dying at some point.